The Palace of Culture and Science – Where does it stand?

In 1955, a square embellished with a building gilded heavily in Stalinist style stamped its mark across the centre of Warsaw, in an act of Communist clout so violent it rocked the very foundations of the city.

The Palace of Culture and Science found a place in Warsaw very rapidly after the end of the war. The idea had been ‘gifted’ by Stalin to the city by 1952, and architects decided its position should be in the centre of the metropolis as a visible reminder of Polish-Soviet ‘friendship’. Some have concurred that the building does display hints of Polish architecture – but nevertheless, its dominating erection was a shock for the Warsaw population: it dwarfed the ruins of the city’s last built skyscraper, the Prudential, and sat atop a literal mound of rubble, with the area for the Palace hastily bulldozed before its creation, even though a few buildings on nearby streets were barely damaged by the war.

Most on the pre-Palace environment had, however, already been lost to history. The streets which once stood under the Palace’s gargantuan wings now exist only in historians’ accounts, with many, such as Magda Stopa, detailing impeccable tenement flats brutally vanquished by the Palace, although other historians mention miserable streets with lack of infrastructure. Nevertheless, the cityscape that the Palace subsumed, street by street, was a rich vision of Warsaw life – as the ever-changing area is today.

Śliska Street

Śliska was the most northern of a series of roads (Sienna, Złota, Chmielna) which were decapitated by the Palace. It was officially recorded in around 1767, and consisted of wooden and brick buildings at first, which were later redesigned into stylish tenement houses.

“At the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, she was known for the “alcoholic aggregate”: distilleries and the well-known brewery of Michał Rydycki. On this street, it was really difficult to keep the balance (slippery …).” Jerzy Wojcik

Pre-war photographs depict a street consisting of various elegant facades slotted neatly together, with delicate balconies jutting out into an immaculately cleaned road. Many pre-war celebrities resided there, such as Władysław Szpilman and his family.

A thoroughfare had been planned for the area in 1939, cutting through Śliska, Złota, and Chmielna, but work never started due to the costs of buying land in such a densely populated area.

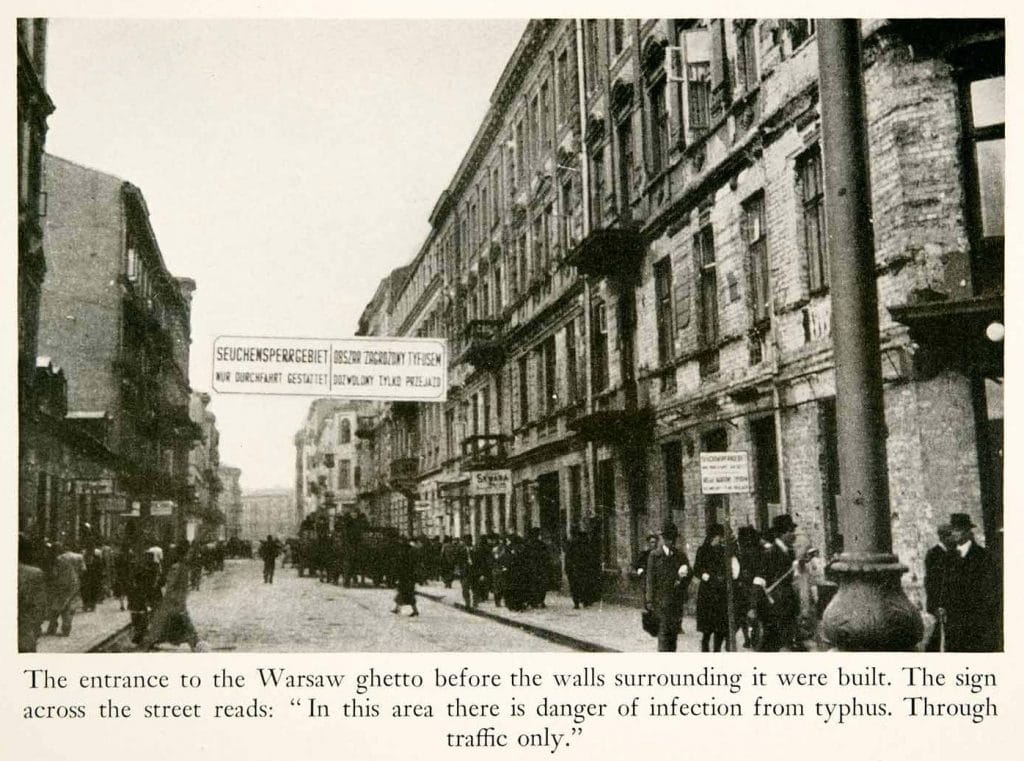

Śliska was damaged heavily in the first bombing raids on Warsaw, and then in 1940, it was included in the Warsaw Ghetto, along with Sienna and a section of Wielka.

As was the case with Sienna, Złota, and Chmielna, half of its length was cut short by the creation of the Palace, with a remnant of where Śliska once lay visible on a small sign in the centre of a zebra crossing by the Palace.

When the planned 1939 thoroughfare finally came to fruition with the creation of Aleja Jana Pawła II in 1955 (name changed 1990), these three streets suffered another incision.

Today, Śliska backs onto the daringly modern Intercontinental Hotel.

Sienna Street

Ulica Sienna was officially named in 1770, though even then showed glimpses of its later beauty, with one segment of the street allegedly containing an avenue of trees. Though at first it consisted of a small number of wooden houses, by the mid 19th century it was extended and built up with further houses and brick buildings. By 1870, the wooden structures were demolished for tenements of four or five floors. After number 5/7 was built with an Art Nouveau façade, this trend for the street’s aesthetic took off, continuing into the interwar period, with multiple well-known architects designing new constructions along the road.

It was also included in the Warsaw Ghetto, and a segment of the Ghetto wall is still preserved behind the modern buildings that are now established along the street. The street also held extensive action in the Warsaw Uprising, much like Sliśka.

Sienna today is one of the quietest of the other four streets in terms of modern developments.

Złota Street

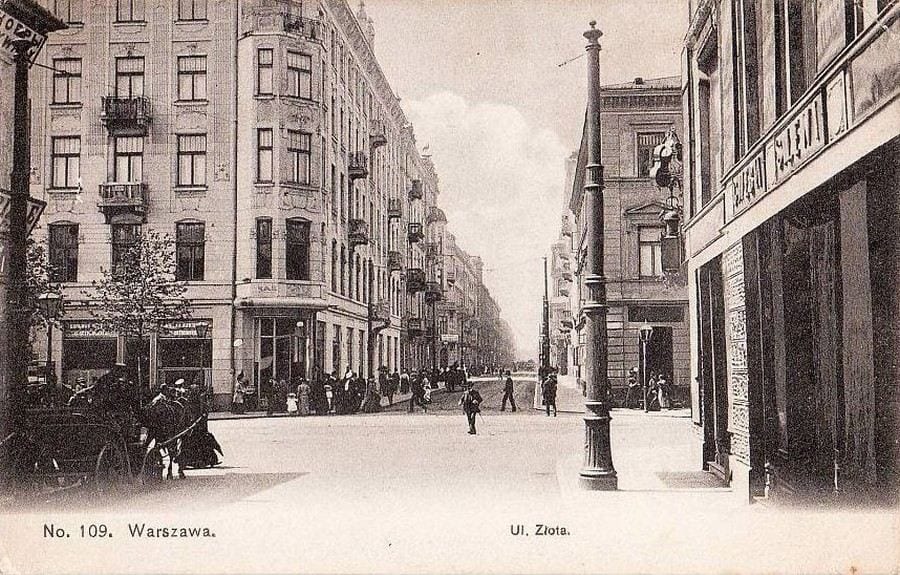

Złota was also named in the late 1700s, though only consisted of only a few buildings. It was only in the mid-19th century that the street exploded onto the Warsaw scene as a central hub, with luxury shops, factories and houses peppered down its path. From 1908, Złota was included on the rapidly increasing tram map, with three lines eventually working their way down the narrow street. Alleged, the increase in traffic throughout the interwar period meant that, in early 1939, the authorities decided to cease this venture. It was permanently altered after the war with the construction of the Palace.

It now hosts the 5th tallest building in Warsaw, the icy, saber-like Złota 44, as well as Warsaw’s most known shopping mall, Złote Tarasy.

Chmielna Street

Chmielna was also named in 1770, but was poorly built up until the late 1800s, despite the efforts of some architects who had transferred the English neo-Gothic style to some new buildings. It was after an alleged fire in 1874 that the street blossomed, finally taking advantage of its proximity to the Warsaw-Vienna station. The popular interwar record company Syrena Electro was based there from 1911, meaning it became a locus for artists and the intelligentsia. Lively with theatres, hotels, cafes, clothing shops, all housed in gorgeous buildings typical of pre-war Warsaw, Chmielna came into its own in the 1930s. In 1938, the railway station Dworzec Główny was finally completed, replacing the old Warsaw-Vienna station.

But the war caused significant damage to the street, mainly due to its transport connections. In 1955 the street was severed into two at its very heart by the creation of the Palace of Culture.

It is now home to the sapphire-glazed Warta Tower, but building plans have already started on what will be its most prominent building yet: the svelte Varso Tower. Varso is scheduled to be the fourth tallest building in Europe, and the highest in the EU, just overtaking the Shard in London. The building will, therefore, be Warsaw’s tallest, and dwarf the Palace of Culture and Science for the first time in history.

Chmielna will finally be victorious.

Ulica Wielka

Wielka cannot be found on a map today, though it was perpendicular to the four other streets, and so was equally significant in the pre-Palace map of Warsaw. It had already lost some of its length by the construction of the Warsaw-Vienna station in 1844, but by the interwar period it was packed with multi-storey tenement houses, much like the other streets. Parallel to the bustling Marszałkowska, it was known as a secondary road to its much more famous neighbour, but nevertheless became a busy and energetic street in the pre-war period.

For the 50th anniversary of the building of the Palace, a poet published a short limerick on Wielka, capturing the nature of the street before and after the Palace erupted onto the scene:

Była tu ulica Wielka,

Serce miasta – sto kamienic,

Teraz wielkie wokół nic,

Straszy na przepastnym placu

Z wykrzyknikiem w kształt Pałacu.(There was a street called Wielka,

The heart of the city – one hundred tenements,

Now great around nothing,

It is haunting the vast square

With an exclamation mark in the shape of the Palace.)

A Changing City

Sadly, the Wielka lyric seems to still have some truth today: the once populous areas in Warsaw’s city centre have been replaced by empty areas, jarring modern skyscrapers and financial hubs.

The old Warsaw can only exist in our imaginations now.

At OddUrbanThings we strive to make your life in Warsaw easier and more exciting.